Peregraf- Ghamgin Muhammad

Shawnm Abdullah is desperate to find her two children who went missing in the chaos of the chemical attack on Halabja in 1988. But she has received no help from the government in her quest to locate them.

She is the co-president of the Halabja Missing Children’s Organization, a group working to locate and reunite families with the missing children, who are now adults. The pain of their loss is felt acutely every year on March 16, the anniversary of the attack.

"The failure of the government and the authorities to fulfill their promises to the families of the victims of Halabja and the families of the missing children has disappointed everyone," Abdullah told Peregraf.

"They did not do any detailed work for us in order to find our sons and daughters so that we can be happy again," she added.

Her organization recently helped Kurdawan find his family using DNA testing. Now 38-years-old, he claims that an Iraqi army officer brought him from Halabja to Baghdad when he was a toddler.

Kurdawan spent several years in the Iraqi capital before being sold to a Kurdish family in Kirkuk for 10,000 "Swiss dinars." He lived a normal life and was known as Hawre until two years ago, when his adoptive father passed away. This precipitated a dispute of his inheritance and his adoptive mother revealed his past, declaring: "Let him look for his family in Halabja."

"I am the son of a Halabja family. My real mother has died and, according to the court's decision, Mahmood Fatah is my real father," Kurdawan told Peregraf. The court ruling is based on a DNA test conducted in Baghdad, which found that he was one of Halabja’s missing children.

"I have been working on legal procedures for a year and, according to research by me and my mother’s family, I am Kurdawan and Fatah is my father," he said.

The case is controversial and has been widely discussed on social media because his father has rejected Kurdawan’s claim of being his son. Fatah told Peregraf that he planned to file a legal complaint against Kudawan, saying that his son by that name died in the attack and that he buried him with his own hands.

To bolster his counter-claim, Fatah had his DNA tested by a lab in Sulaimaniyah, which found that it did not match with the man claiming to be Kurdawan. The latter suspects that the results were manipulated because a separate test in Baghdad found a DNA match.

"We have sent DNA examinations of Mr. Hawre and Mr. Mahmood to the court and, according to our examinations in Sulaimaniyah, the two individuals are not similar. That is that: they are not father and son," Farhad Barzinji, an expert in molecular biology, told Peregraf.

DNA is the genetic foundation of all life — from bacteria to humans — and is passed down from generation to generation. Children inherit DNA from both parents. There should be no less than a 99 percent DNA match between parents and children and no less than a 96 percent match between siblings.

"There is no mention of DNA in the Personal Status Law, so it is not enough for proof of origin if witness testimony does not support the claim," lawyer Shalaw Abubakr told Peregraf, adding that determining family origin is a sensitive issue so that the father’s contention should not be denied.

Under Articles 52 and 53 of the Personal Status Law, a father must acknowledge a child’s claim for it to be legal. Moreover, there must be proof of the child’s origin, including a witness who is aware of the child’s existence who can prove it in front of a court.

Beyond debates over DNA testing, the major problem for victims of the Halabja chemical attack is the lack of government assistance in searching for their lost loved ones. Since the creation of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), there has been no official or unofficial effort to locate those who are missing, beyond the activities undertaken by the families themselves.

Abdullah noted the case of Alan Tofiq Karaba, one of Halabja’s missing children who was able to reconnect with his family. He is now a representative of the Halabja Missing Children's Organization.

"Alan has given evidence that, at the time of the Halabja chemical attack, 18 Kurdish children under the age of 11 were imprisoned in Iran and Pakistan. They are getting older and no one has asked about them yet," Abdullah said.

The KRG’s Ministry of Martyrs and Anfal Affairs said that there are approximately 75 families who have missing children and the whereabouts of an estimated 200 individual children are not known, but the tallys differ across organizations.

Peregraf spoke to a number of families who lost their children during the attack, but they spoke on condition of anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the topic and the controversy that has been stirred up on social media by the case of Kurdawan and Fatah. They are concerned about how DNA testing is conducted in the Kurdistan Region.

"Today a child belongs to you and has returned and tomorrow, from another test, he or she is not yours and they become a foreigner. You will lose your honor too and we are afraid that we will face social problems," said one person.

This fear has been bolstered by disputed DNA results. Some who were identified by tests conducted in Sulaimaniyah later found discrepancies in the results.

In February, Brigadier Tariq Ahmed, police chief of the Kurdistan Region, stressed that the government was offering free paternity tests to those who may be missing children. He explained that the tests are conducted with the newest technology and adhere to international standards.

According to Xzmat, a website operated by the KRG, however, test results take seven to ten days to be processed and cost 250,000 Iraqi dinars ($171) per test.

In November, the KRG Council of Ministers created a committee to coordinate the response to the issue of the missing children. It is chaired by a representative the martyrs ministry and also includes officials from the interior, justice, and health ministries and the foreign relations department.

"This board is the only official organization in the KRG to work on the issue of the missing children of Halabja," Adil Salih, spokesperson for the martyrs ministry told Peregraf.

The committee has met with the Iranian consulate in Erbil and plans to send a delegation to Iran in the near future. Additionally, it will carry out testing and provide legal documentation and support for anyone who requests a DNA test to discover if they are one of the missing children.

"DNA laboratories belonging to the interior ministry will be inspected and, if the committee decides, the investigation can be conducted abroad," said Salih.

According to the Halabja Victims' Association, eight children have been reunited with their families so far. There are five others claim to be missing children, but their cases have not yet been resolved.

"The government has not yet provided enough assistance for the cases of missing children," Luqman Abdulqadir, head of the Halabja Victims Association, told Peregraf.

"The [KRG] committee is being discussed and has just been created. If it works, the cases can be better resolved," he added.

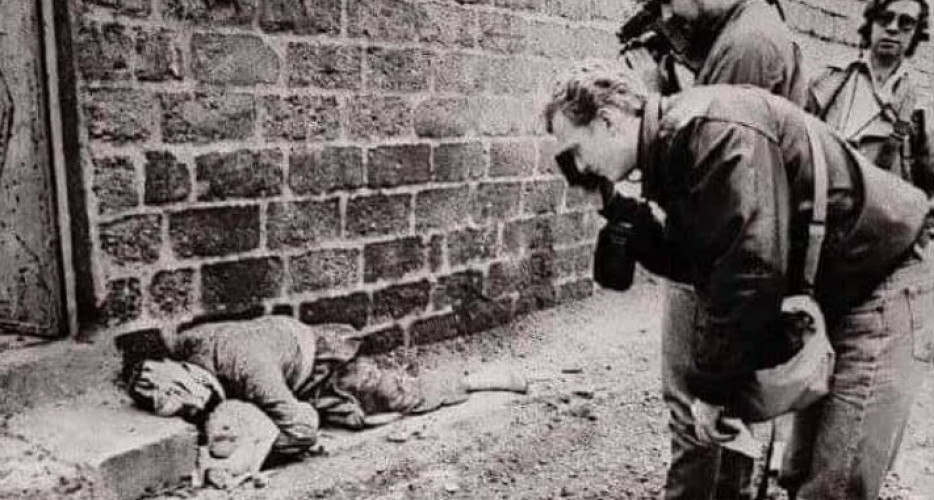

In the 1988 attack, approximately 5,000 civilians were killed and thousands of others were injured and displaced. Many of those who were exposed to the toxic chemicals still suffer from their effects.