Peregraf- Surkew Mohammed

Journalists are heavily criticizing a new directive recently issued by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), arguing that it will restrict press freedom and is dangerous for journalists and media outlets.

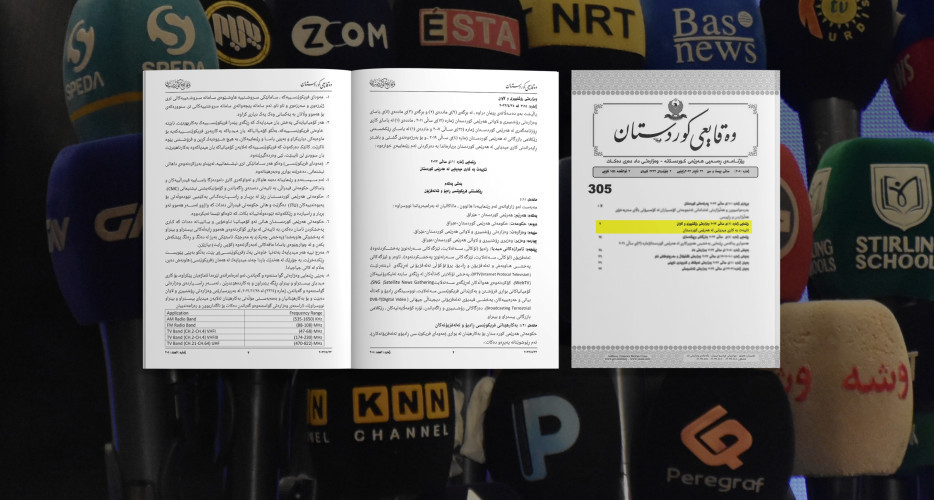

On May 22, the KRG’s Ministry of Culture and Youth released Directive No. 1 of 2023, which has been published in the government’s official gazette, Waqi'i Kurdistan. It outlines new rules regulating media work in the Kurdistan Region and declares that its 17 articles will be applied with the same legal force as the Kurdistan Region’s Press Law.

According to the directive, audiovisual media, users of social media, and advertising companies must comply with the new regulations within three months or face legal consequences.

Dr. Saman Fawzi, a university professor and expert in media law, said the ministry’s new directive contradicts elements of the Press Law.

He told that the directive is "so bad that it is not useful to amend and should be rejected because there are many dangerous points for journalists and media outlets,” adding that journalists should send a letter to Minister of Culture Mohammed Said Ali requesting that he suspend its implementation.

The KRG has defended the directive as necessary to regulate local and satellite television channels, radio, electronic media, and social networks.

The language of the Press Law is specific to written media and newspapers and does not refer to other types of media. However, the courts routinely use the Press Law for cases involving television and online media.

Fawzi said that the KRG is overstepping its authority and that problems with the Press Law must be addressed either legislatively by the Kurdistan Parliament or by an independent body that is not affiliated with the government.

“Even in [federal] Iraq, the Independent Media and Communications Commission does this and issues licenses to channels," he said.

What are the dangers of the directive?

The Ministry of Culture's directive tightens the licensingprocedures that channels and outlets must go through, increases license fees, and gives the ministry the authority to monitor published content and restrict what material outlets are allowed to broadcast.

Under the new directive, the Ministry of Culture is responsible for issuing licenses for outlets, but the owner of the outlets mustalso receive approval from the Ministry of Interior, which have 90 days to reply. There is no ability to appeal against a decision by the interior ministry.

The directive increases the license fee for satellite channels to 40 million Iraqi dinars ($30,572), local television stations to 20 million Iraqi dinars ($15,286), radio stations to 10 million Iraqi dinars ($7,643), and broadcasting companies to 20 million Iraqidinars.

It also sets 22 requirements with which audiovisual mediabroadcasts must comply. However, many of these are vague, open to interpretation, and contradict the Press Law.

For example, the directive prohibits outlets from publishing content that allegedly harms national security and the public interest, promotes activities that cause economic crisis or disruptthe market, offends spiritual beliefs, or is strange and harmful to Kurdish culture and society.

Another point contained in the directive states that outlets must comply “with the standards of media content issued by the [KRG’s] Department of Media and Information." This means that the government will have final say over what is publishedby media outlets from now on with the threat of legal sanction hanging over those who do not comply.

Under the new rules, outlets are not allowed to publish statements from people accused of crimes before they go to trial. In practice, the police and security agencies routinely do so by posting videos of confessions on social media before defendants go before a criminal judge.

The broadcast restrictions introduced by the directive go beyond journalism. One provision states that foreign dramas “that encourage murder, suicide, marital infidelity, and cheating should not be bought or broadcast.”

All audiovisual and broadcast media will also now be monitored by the Ministry of Culture in order to record violations.

Outlets that run afoul of the directive will first be issued with a warning, followed by a suspension for a second offense. Those that rack up five violations in two years will be blacklisted and barred from any interaction with any KRG ministry for one year.

"By issuing this directive, the duty of the Ministry of Culture has been completely changed to a ministry to suppress freedom. The directive is a retreat from the Press Law," journalist Shwan Mohammed told Peregraf.

The Metro Center for Journalists’ Rights and Advocacy has called for the new rules to be scrapped.

"The directive is a policy of restriction on freedom of expression and will nullify the content of the Press Law," Diyari Mohammed, director of Metro Center, said.

Regulation of electronic media

The section of the directive about electronic media is proving especially controversial due to its lack of clarity about whether it regulates journalistic activity or not.

The first article of the section says that it “does not apply to journalism and journalists,” but the next article states that it applies to "pages, portals, and groups in communication applications, electronic media portals, and web TV. “

Fawzi told Peregraf that it is not clear to him whether the second article includes online newspapers and social media used by journalists.

The KRG already has a law that covers social media, the Communications Device Misuse Law, which was passed by the Kurdistan Parliament in 2008 to prosecute people who use phones and social media to harass and defame others.

This law, however, has regularly been used in the past to prosecute journalists who post content online that is critical of the authorities. Many fear that the new directive will further empower the authorities to restrict freedom of expression.

Despite the lack of clarity about what and who the section on electronic media covers, this section of the directive prohibits publishing fifteen types of content online or via electronic communication.

This includes anything that allegedly disrupts social harmony, directly or indirectly causes the defamation of persons and national symbols, matters that jeopardize the public interest such as introducing doubts about freedom of expression, economic policy, national security, and any other public interest.

None of these are clearly defined and can be viewed as contrary to basic democratic principles.

It is also prohibited to disclose “letters, telegrams, or other documents that are not authorized for public release by government bodies” or to publish “any article or rumor that defames someone or reveals the secrets of someone's life, even if it is true.”

Such activities can only be approved through the courts, but no procedure for doing so is outlined by the directive.

Under these rules, for example, even if there is evidence of corruption on the part of government officials, an article about it cannot be published because it would tarnish their image.

Peregraf contacted several officials at the Ministry of Culture to obtain more information and to clarify the points of the directivethat are unclear, but they declined to comment. They claimed that they had only seen the directive after it had been published.

One of the officials said that "the prime minister's office had a hand in preparing the directive with the media and information department and the minister of culture,” referring to KRG Prime Minister Masrour Barzani and Minister Ali.

Barzani is a member of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Ali is a member of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK).